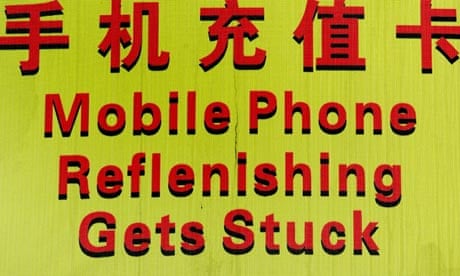

Upsetting news for English-speaking residents in China: "Chinglish" is apparently being wiped out. Chinglish is the name given to the grammatically incorrect or misspelt English found predominantly on signs in parts of China. The language style has attracted a cult following, with a Facebook group, Flickr pages and even a book dedicated to the subject.

But there are fears that Chinglish could be killed off before really having a chance to flourish. Reports suggest that authorities, wary of the embarrassment some examples of Chinglish could cause prudish visitors to next year's World Expo, are launching a drive to correct the quirky mistranslations.

Before we officially declare Chinglish to be a dead language, we should note that this isn't the first such drive to wipe it out. On the website of the German broadcaster Deutsche Welle (bear with me), in an interview with the Chinglish enthusiast Oliver Radtke in May, it was pointed out that "in recent years, China has kicked off campaigns to root out poor English grammar and misused vocabulary in official usage", including one before the Olympic games in Beijing last year. Judging from the examples that continue to flood into internet groups, the success of these campaigns seems to have been limited.

Radtke is a staunch supporter of what he describes as the "wonderful results of an English dictionary meeting Chinese grammar". He insists that his interest in Chinglish is about "passion not mockery", and most online groups seem to echo this, looking upon Chinglish with affection rather than scorn. The "Save Chinglish" Facebook group has attracted more than 8,000 members and more than 2,500 Chinglish examples, while members of the Flickr group The Chinglish Pool have contributed more than 3,000 photographs.

So what is it about Chinglish that has attracted such affection? Examples on the sites above range from amusing misspellings in menus – "Three testes ice cream", anyone? – to simple grammatical errors – a sign by a lake imploring visitors to "refuse to feed" the (presumably persistent) birds.

The best ones, as Radtke says, are where English words are used with Chinese grammar, often with incorrect spelling thrown in for good measure. These can range from the strangely poetic – "the rust embroidered shoes approve the zero concurrent y camp" – to the genuinely mystifying – "pood taken late at night breakfast".

Will the latest push succeed in wiping Chinglish out completely? It seems unlikely, but perhaps visitors to China will have to look that little bit harder to be warned to "be careful about a landslip" in a bathroom or "take notice of safe: The slippery are very crafty" on a hillside.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion