Stress

Do Tests Stress Out Your Child?

Emotional states—especially stress—can impact your child's success on tests.

Posted June 19, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

If the title of this post caught your eye, you‘ve likely experienced your children's emotional states impacted by test stress. Test stress has repercussions on test outcomes and kids' emotional well-being. Test stress can show up in many ways—such as fear of failure, feeling sick before a test, a mind-numbing sense of doom during the test itself, and emotional struggles after receiving the results.

Test stress is an example of how one’s emotional state strongly influences how the brain directs thoughts, behaviors, and actions. Because children's and teen's brains are still building their neural control centers, their emotional responses tend to be magnified and, at times, overwhelming. Although children's emotional responses to test taking may not be as dramatic as their mood swings, door slams, or eye rolls, these stresses profoundly influence their test-taking success.

Despite the frustration we feel about high-stakes testing of children, these tests are entrenched as part of the current educational experience. These standardized "fill-in-the-bubble" tests often inadequately assess what children know, and numerically compare kids against one another. These are limited assessments of their inherent knowledge, often just reflecting memorization and the parroting back of data.

The good news is that you can take action to help your children reduce their test stress responses and succeed in demonstrating what they do know. Knowing how to help children reduce test stress can enhance their ability to approach these tests by applying their highest mental potential.

The Neuroscience of Stress

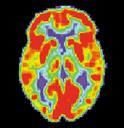

Neuroscience research continues to reveal the impact of high-stress environments on learning and memory retrieval.

For information, such as something you read, hear, or study, to reach memory storage, it must pass through other regions of the brain. One gateway in the path of learning to memory is the amygdala. The amygdala can be thought of a switching station that routes incoming information to either the "high" thinking brain or low "reacting" brain, depending on one’s stress level.

In a neutral or positive state, information can flow through the amygdala into memory circuits unimpeded where it is available for recall. When in a high-stressed state, the amygdala limits information access to higher brain memory and reasoning controls. Stress triggers high metabolic activity in the amygdala resulting in reduced access of information to higher brain memory storage. In addition, as the reactive brain takes over, it prompts a narrow set of behavior responses similar to the survival-oriented reactions of other mammals: fight, flight, or freeze. When your children are in that negative stress state, there is limited access to the higher cognitive abilities, memory, and judgment required to evaluate test questions and respond with their highest potentials.

Build Their Self-Awareness About Tests and Stress

Many kids feel enormous pressure regarding tests. Help them take control of those stress feelings to avoid the amygdala's red-light response blockade. By guiding children to build emotional self-awareness, they can recognize burgeoning stress and initiate self-calming practices.

Help them build self-awareness of their own emotional states by asking them to think about and describe the signs that they feel go along with feeling stressed, anxious, fearful, angry. Younger kids can evaluate their impressions of what emotions might be felt by characters in picture books. Older kids, especially with school and test stress in mind, might see if they feel overwhelmed and out of control with physiologic effects such as increased perspiration, rapid heartbeat, sense of being dizzy in the test room.

With increased awareness of their stress signals, they can activate their destressing strategies before the amygdala blockade takes over. Because of the brain's neuroplasticity*, each time you guide children to recognize, name, predict and plan interventions for their test stress, they build stronger neural circuitry. They will have stronger wiring with easier access to keep in control of recognizing and then reducing their stress.

Examples of stress reduction techniques you can guide your children to practice and build include:

- visualizing positive memories

- mindful breathing

- optimistic envisioning of something they look forward to

- counting to 10

Reduce the Negative and the Increase Positive Expectations

- Many tests don’t allow children to show what they know. Excessive emphasis on rote memorized facts does not really characterize what children understand—rather, just what they can parrot back. Parents can offer one of the most valuable lessons by affirming that, indeed, their children are far greater than the sum of their test results and that mistakes provide opportunities to learn.

- Have discussions with kids explaining that incorrect answers on homework, quizzes, or tests do not mean they are not smart, but rather that they are going through the learning process. To really learn means to go from not knowing to knowing, and of course, there will be mistakes along the way, just as there were when they learned to ride a bike or play an instrument. Share with them your memories about their setbacks on the roads to their successes. Remind them of how they may have been discouraged, but persisted, and succeeded.

Test Day Tips

1. Prior to starting the test, suggest they write their frequent errors on scrap paper they are given to use during the test (if permitted) as a guide to have during the test taking and to review again when they check their tests.

Examples of frequent errors:

- Not looking carefully at what is asked.

- Prematurely selecting an answer without reviewing all the options.

- Not using estimation to see if a math answer is reasonable.

- Forgetting to check that their answers are correctly in the place corresponding the question number.

2. Similarly, on scrap paper (if permitted), they can reduce some stress by writing what they are "holding in their heads." These are things they studied, but harder for them to remember when they are nervous (e.g. formulas, dates, procedures, definitions, etc.). This downloading can serve as "external memory storage" and reduce their stress that could reduce their retrieval of what they have stored in memory.

3. Your children can, in advance, create their own abbreviations or anagrams of the pertinent information they either want to remember for the test or for how they want to evaluate test questions and their answers during a test. For the latter, WREN: W (What is asked?), R (Read all answers before choosing), E (Estimate if the result they calculated for a math or science question is reasonable), and N (Numbering on answer sheet).

Conclusion

When kids have the parental support, emotional awareness, and practiced skills of emotional self-regulation, challenging tests can be approached in a stress-reduced mental state. Your children can understand the burdens of brain stressors and unleash skills to assume the driver's seat in their emotional self-regulation. Armed with confidence, they can direct their brain to recognize and respond to the test-stress activating cues and achieve success.

* All brain memory circuits holding skills, knowledge, habits of mind, and executive functions are strengthened by use (neuroplasticity, where more firing ((activation)) results in stronger wiring ((connections)). Activating a neural network containing the information for a skill, technique or memory is what turns on the neuroplastic response, that then myelinates a stronger and faster network, for memory stability and timely recognition. When skills of awareness of or responses to feelings of stress are practiced, especially with guidance, the durability and strength of these networks increase through this same neuroplastic response. In turn, these strengthened networks help children resist automatic, reactive responses; stay in the moment, settle their mind states, and connect with the task or test at hand.