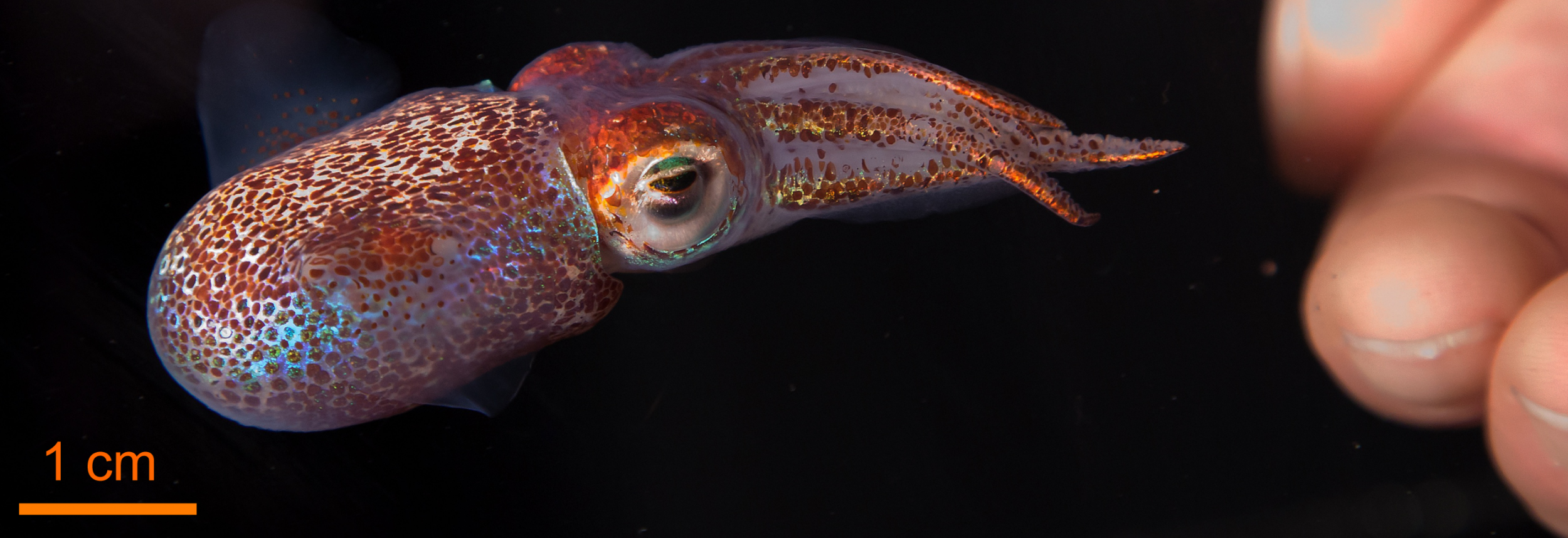

One squid has a unique solution to keep her eggs healthy, according to new research—bacteria and jelly.

For the Hawaiian bobtail squid, the fungus Fusarium keratoplasticum is a deadly threat to its eggs. If the fungus reaches the eggs, it covers them, and the embryos die. However, the female bobtail squid has developed a talent that keeps them protected—but using a special organ, according to research presented on Monday at the 7th Conference on Beneficial Microbes.

The accessory nidamental gland is only found in cephalopods including the female bobtail squid. This gland can keep and then secrete bacteria, such as Verrucomicrobia and Rhodobacteraceae. Hawaiian bobtail squids don't develop their sexual organs until a few months after they hatch, so a female squid will develop this gland at two to three months old. It will then most likely collect the beneficial bacteria from its environment. When the squid is ready to lay eggs, it will first wrap the egg in clear jelly, then the bacteria before laying them.

Spencer Nyholm, associate professor in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at the University of Connecticut, told Newsweek he asked the question, "What are the roles of these bacteria, and could they actually be protecting these squid eggs?"

Nyholm and his team treated the jelly with antibacterials, which got rid of the bacteria that would normally envelop the eggs. Instead of the eggs eventually hatching, fungus covered the eggs and killed them. This symbiotic relationship between the squid and the bacteria help the squid survive during such a vulnerable time, the new research reveals.

This isn't the only symbiotic relationship between the Hawaiian bobtail squid and bacteria. The nocturnal squid partners up with Vibrio fisheri, a bioluminescent bacterium. At night, without these bacteria, the moonlight would light up the squid, opening up the opportunity for predators to notice it. Instead, these glowing bacteria live inside the squid and illuminate its bottom. When the squid swims over other sea life, its glowing underbelly looks like the moon, and the squid stays safe.

In that relationship, the bacteria are provided a safe place to live with easy access to food. In the relationship of the female's accessory nidamental gland, the bacteria get the same benefit.

In this latest research from Nyholm's team, which is still under peer review, he's found that the relationship in the accessory nidamental gland might not only be beneficial to the squid and to the bacteria, but to humans as well. The Marcy Balunas Lab at the University of Connecticut found the bacteria can also attack the fungus Candida albicans, which infects humans. "Can we discover novel antifungal compounds?" Nyholm wonders.

Fungal infections in humans, animals and agriculture can be really difficult to treat, and there aren't many effective drugs available, Nyholm notes. He says, "We're hoping that by studying these bacteria we can actually discover some new treatments."

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified the bacteria that attacks Candida albicans.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.