The star-nosed mole has one of the "weirdest" snouts in the animal kingdom. Now researchers are uncovering fascinating new insights into this unusual body part.

The star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata) is a highly specialized semi-aquatic mammal found across a vast swathe of eastern North America, including parts of Canada and the United States.

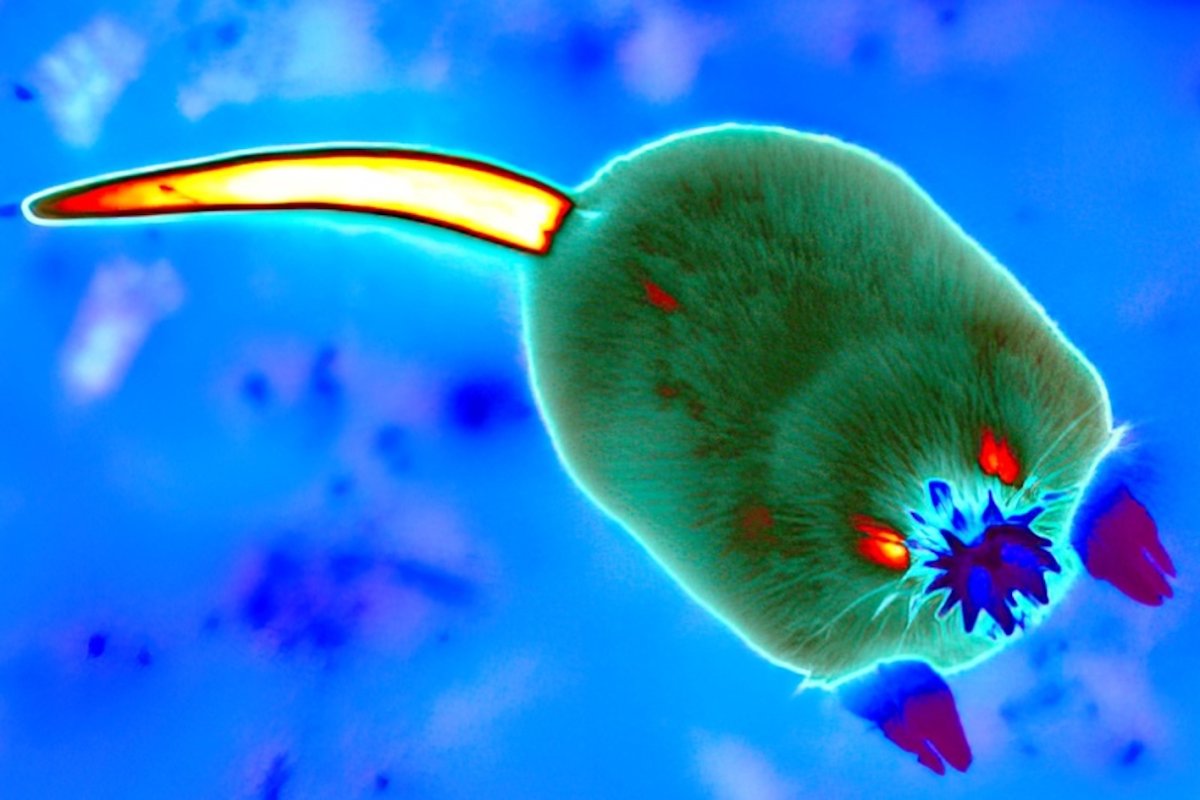

Inhabiting wet lowland areas, this five-inch-long mole is renowned for its strange snout that features 22 tentacles.

"The conspicuous 22-tentacled snout of the star-nosed mole is among the 'weirdest' evolutionary novelties on the planet," Glenn Tattersall and Kevin Campbell told Newsweek.

Tattersall is a professor of biological sciences at Brock University in Ontario, Canada, and Campbell a professor of environmental & evolutionary physiology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada.

Tattersall and Campbell have been studying this unusual creature and published a study this month on the topic in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

The nose is superficially reminiscent of a hand featuring fleshy and mobile finger-like appendages called "nasal rays." But, unlike an elephant's trunk, they are not used for grasping, the researchers said.

Instead, the rays function much like an eye so the predator can rapidly survey its mostly subterranean environment in search of invertebrate prey. The moles are practically blind and can detect only vague light versus dark.

The highly specialized nose of this species "evolved to rapidly detect and consume hundreds of tiny prey items per day, thereby opening a new ecological niche for this species that is unavailable to other mole species," Tattersall and Campbell said.

This hunting behavior is facilitated by the unique nasal appendages, which are incredibly touch-sensitive. The splayed-out nose is only about as large as a fingertip. But this small space packs around 25,000 to 30,000 tiny, dome-shaped sensory organs that cover the surface of each nasal ray.

These touch receptors—known as Eimer's organs—are found only in moles but are particularly common in this species. In the case of the star-nosed mole, the organs have more than 100,000 touch-sensitive nerve endings.

Taken together, this means the animal's nose is the most touch-sensitive organ among vertebrates. By comparison, an entire human hand has only around 17,000 touch receptors.

"Thus, the tentacles are primarily used to detect or distinguish (mostly) tiny prey items the moles search for within the soil and underwater," Campbell said.

"Star-nosed moles are also known for the rare ability to smell while under water. They do this via the rapid exhalation and inhalation of bubbles, so allowing chemical odorants on prey items to be detected. This almost certainly helps them not only to confirm the identity of prey items, but also to assess whether or not they are edible."

The speed of the star-nosed mole's searching behavior is also "astonishing," according to the researchers. This ability makes them one of the fastest foragers in the animal kingdom.

"Previous research has demonstrated that the star is able to make up to 13 searches per second and locate, identify, and then ingest individual prey items in as little as 120 milliseconds," the scientists said. "By comparison, it takes us humans about 200 milliseconds to register a traffic light change and begin moving our foot off of the brake pedal."

The species is also unusual among moles in that it is found far more to the north than other species. In addition, it is only one of three mole species that is semi-aquatic.

"Intriguingly, then, this species often contends with foraging in sub-zero degree Celsius environments for more than six months a year," Campbell said. "As many terrestrial prey items hibernate in the winter, the moles also spend a considerable time foraging in near-zero-degree water during this season."

Uninsulated appendages like human fingers quickly lose their agility and touch-sensitivity in cold water. Because water conducts heat nearly 30 times faster than air, attempting to keep the nose warm would pose a formidable challenge for this small mammal. This conundrum is where the idea for Tattersall and Campbell's latest study originated.

"As thermal biologists, we had both wanted to study this potential thermal-sensory conflict for more than a decade," the researchers said. "Briefly, there are only two possibilities: either the mole heats the star—at extreme energetic cost—as a requirement to maintain a high sensitivity; or it allows the star to cool and has some apparent work-around for sensitivity while cold."

Fortunately, Tattersall and Campbell were able to examine these possibilities in summer 2022, while helping to film the animal for a wildlife documentary.

"Our aims were really quite simple: to determine, indirectly, if there are any obvious changes in blood flow to the nasal rays when they are exposed to warm versus cold temperatures," the pair said.

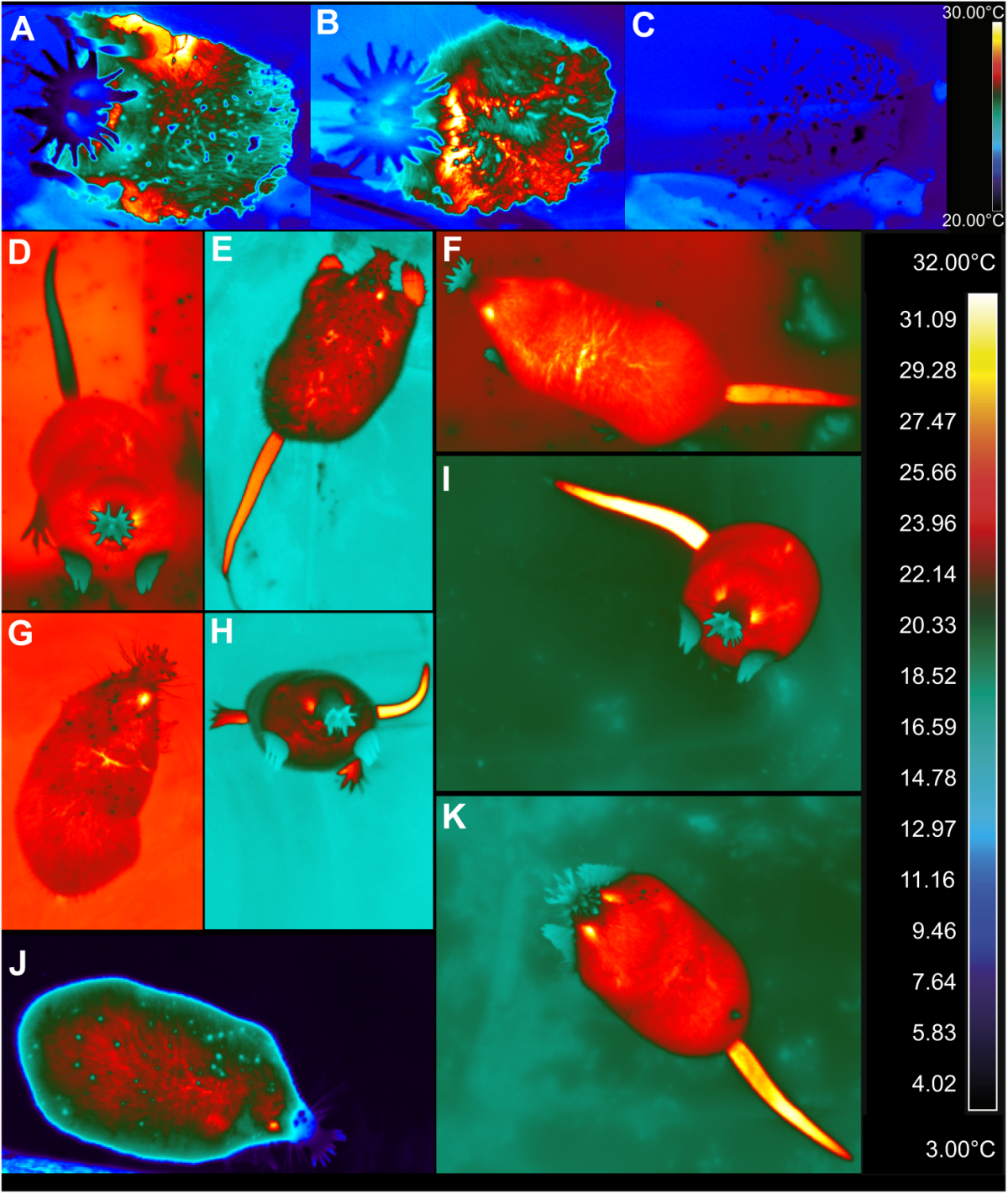

To do this, the researchers studied three captured star-nosed moles with a high-resolution imaging camera. The thermal camera was used to work out nasal blood flow from changes in the star's surface temperatures.

The scientists placed the moles into a viewing chamber that was kept cold, warm or at room temperature. Since the moles search for food in the water and on land, the chamber bottom also contained either cold (around 2 degrees Celsius, or 36 degrees Fahrenheit) or warm (around 30 to 32 degrees Celsius, or 86 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit) water.

The thermal camera was rolling continuously and able to measure the body surface temperature of the moles throughout the experimental trials, the scientists said.

"The premise is pretty simple," Tattersall said. "Since the nasal rays are naked and fleshy, if there is continuous blood flowing to them, they would appear warmer than the water or air temperature. By contrast, cold surface temperatures are indicative of low blood flow or very efficient and extensive insulation—for example, fur looks cool in thermal images since heat is trapped underneath and not getting through."

The duo's key findings were that the fleshy tentacles do not need to be kept warm for the star-nosed mole to sense its prey efficiently. Instead, the tentacles did not differ much in temperature from the ground, air or water where the moles were poking around.

"Prior work on many other animals has always suggested that there is a relationship between sensory organs and blood supply. Very often, there has been an assumption that these mammalian sense organs require high levels of blood flow to function," Tattersall said.

"The implications behind our findings are likely related to the fact that the star-nosed mole spends most of its life foraging for food in cold water and in wet soil. Having a high amount of warm blood flowing to the nasal rays would be a huge heat sink and cost them a lot of wasted energy in heat loss."

Curiously, anatomical data show from the 1960s showed that the nasal rays have more than enough blood vessels.

"So, the fact that we rarely see the rays 'heat up' suggests that they purposely constrict the blood from going out to the rays most of the time," the scientists said.

The marked expansion of touch receptors in the mole's nose over the course of its evolution came at the expense of thermal receptors, Tattersall and Campbell said. This means the nose is less able to distinguish warm versus cold, relative to the nasal skin surface of humans.

"On the plus side, this would minimize aversion to cold—i.e. the nose likely does not feel numbness or pain like we do when we place our hands in ice-cold water," the scientists said.

"The fact that we don't see the fleshy tentacles 'heating up' further suggests that this species may have evolved this ability as a particularly efficient means to conserve body heat. However, it raises new questions, such as: How are its touch-sensitive receptors able to function efficiently at both high and low temperatures?"

Correction 03/06/23, 12:54 p.m. ET: This article was updated to clarify that elephants do not have prey.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.