“The bugs are not like us. The Pseudo-Arachnids aren’t even like spiders. They are arthropods who happen to look like a madman’s conception of a giant intelligent spider, but their organization, psychological and economic, is more like that of ants or termites; they are communal entities, the ultimate dictatorship of the hive.”

-Robert A. Heinlein, Starship Troopers

Producer Jon Davison was first approached in 1991 for a science-fiction project, initially titled Outpost 7. It narrated the struggle for survival of a group of soldiers, stranded on a remote planet against enormous insectoid extraterrestrials. Writer Edward Neumeier was encouraged to propose the project to TriStar Pictures — but it was turned down. Eventually, it was realized that the idea bore certain similarities to Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers — mainly because giant insectoids were an important driving element of both concepts. “[It] had bugs in it, and we wanted those bugs,” Davison told Cinefex. An adaptation of the novel was thus proposed, and this time endorsed by the studio. To direct the film, Davison approached Paul Verhoeven; although the director found the idea “silly” at first, he changed his mind when he realized the project would be another chance to work with Phil Tippett — an enticing prospect. The two had precedently collaborated in bringing ED-209 to the screen for RoboCop. “I’d found our relationship on RoboCop very stimulating,” the director told Cinefex. “Phil’s a genius-type guy, and ever since RoboCop, I’d been looking for another project to work on with him.”

For Tippett, Starship Troopers represented an opportunity to advance the computer animation techniques whose foundation was made during the production of Jurassic Park. He said: “prior to Jurassic Park, I’d produced stop-motion mostly through traditional methods — by incrementally moving and photographing three-dimensional puppets on a frame-by-frame basis. But our studio’s dinosaurs for Jurassic Park were not created traditionally. Instead, a special piece of equipment, the Digital Input Device, was developed for that picture by a talented guy named Craig Hayes. The DID is a metal puppet armature, rigged with electronic sensors. The sensors record movement information on a controller box that translates it for computer use. When an animator moves the armature by hand, those movements are mimicked by wire-frame representations inside a digital environment.” Essentially, Tippett realized that Starship Troopers was the chance to improve those effects in fields such as software, hardware and render time.

Before any animation began, the effects team focused on designing the castes of Bug society, based on the original story. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers portrays a dystopian future, where humanity engages in war with an alien civilization — the Pseudo-Arachnids of Klendathu, also derogatorily labeled as ‘Bugs’. Despite their apparently primitive appearance, the creatures have advanced technology at their disposal, being able able to conceive and build spacecraft and weapons of war (“stupid races don’t build spaceships”).

The Bugs’ society is hierarchical and caste-based. A Queen is the progenitor of a specific colony. The novel never describes this caste detailedly, and goes no further than mentioning that its purpose is that of an egg-layer. Strategic administration of the society is a task assigned to the Brain Bugs, which — despite their enormous intelligence — depend on lower castes to survive. In fact, they are described as having “barely functional legs, [and] bloated bodies that were mainly nervous system,” and are telepathically connected with the lower castes. The basis of Bug society is composed of the Warrior and Worker classes: the Warriors are “biologically incapable of surrendering,” and move forward in battle with energy weapons. Workers are generally assigned to manual labour — even though they can also be strategically used as decoys by other castes (such is the case during the invasion of Planet P).

The film adaptation’s version of the Bugs (dubbed the ‘Arachnids’) is widely different from that of the novel, with the major departure lying in the fact that the film Bugs have not crafted any kind of artificial technology. This was a decision taken by the director himself. Neumeier explained: “Heinlein described them as looking like spiders, and yet the Bugs seemed to have evolved physically beyond that because they were able to shoot guns and to behave in an anthropomorphic way. This was one of the earliest things Paul Verhoeven and I talked about; and it became clear that our discussions were leading down the path of anthropomorphic aliens, portrayed by actors in elaborate costumes. Verhoeven quickly put a stop to that line of thinking. He told me, ‘I can’t see a Bug holding a gun.’ He did not want to see some sort of man in a suit with a funny crab claw, or a six-foot-tall ant with its head in a space helmet. Eventually, we came up with the idea that we should do the Bugs as bugs, as believable giant insects.”

Designing the Bugs was a task assigned to visual effects supervisor Craig Hayes. The artist recalled in an interview with American Cinematographer: “Because of our established relationship with Paul, we worked out some of the overall issues in the first round. We started by breaking the insects down into a Bug hierarchy, then into individual groups. We did different drawings of Bugs with weird stuff here and there, then fleshed out designs for each particular style; but there was a concerted effort to make them pretty familiar. Troopers is not about this fantastic lifeform: the Bugs had to be real and grounded.”

Brainstorming sessions with Verhoeven included reviews of footage of various insects and other arthropods — with focus on their structure and systems of biological defense. Although no Queens or Workers are shown, the caste system of the film Bugs is far more diverse than the novel Bugs. Hayes explained that “since these Bugs were supposed to be intelligent, or, at least, a whole lot smarter than our homegrown variety, we posited that a hierarchical structure would have evolved within the alien community, mimicking the division of labor seen among insects on earth — workers, drones, et cetera.”

Dozens of design ideas were conceived; ultimately, only six types, each with its ‘function’, were chosen and refined. Since the director was adamant that Starship Troopers was essentially a war film, the creature designs reflected that concept — transforming insectoid creatures into substitutes of World War II Axis troops and exaggerated weaponry from propaganda films of the time. Hayes noted: “to follow up on the ‘World War II in space’ idea, we invented a sort of military analog for the Bug troops. Some would act as foot soldiers, some as heavy artillery.”

Tippett further elaborated: “the Warriors are the ground-based troops, the Plasma Bugs are the heavy artillery, the Hoppers are the air force, and the Tankers are like flame-throwing tanks. Craig tried to create some logical consistency within the Bug community. For example, the Hoppers are genetically mutated Warrior Bugs: they just have legs in different places and differently elongated limbs. In the same way, the Plasma Bugs are genetically altered Tankers: they’re a lot bigger and look significantly different, but there are a lot of similar design attributes. We wanted to achieve a balance with these alien adversaries. We didn’t want you to take it all in or understand what they were the first time you saw them. Instead, we wanted their appearance to manifest itself over the course of 50 shots.”

Even after the initial approval of the project, the studio executives were uncertain as to how the creatures could be efficiently brought to the screen. To erase those concerns, Davison convinced the executives to fund a “Bug test” — on a $225,000 budget. The footage was not only crucial for further development of the film, but also a chance for Tippett Studio to establish how to render the creatures — especially the Warrior Bugs themselves, whose design was finalized by the time the test was filmed.

The test footage was screened for studio executives, and proved that the Bugs could be successfully brought to the screen. Tippett recalled: “we went to pitch it and it went up the food chain at Sony, and showed them what we were doing. They would worry about things like, ‘where’s the mouth on the bugs?’ We’d go, ‘It’s that little hole there.’ They’d be like, ‘well, how do they eat?’ We’d say, ‘well, they eat sap from the queen back in the cave.’ They’re like, really? But if they don’t have mouths, they can’t kill people.’ I go, ‘no, they’ve got these big beaks that can chop people in half, and they’ve got these things that can skewer them, so they just kill people. They don’t eat people. They don’t care about people.’ Then we had to go through the hierarchy of screening for three different executives, and at that time Mark Canton was the head of the studio. He brought his entourage in, and they looked at it, and he turned around and said, ‘Well, is this movie going to be fun?’ We’re like, ‘Yeah. Sure, it’ll be fun.’ So he said, ‘Okay, go ahead and make it.'” Starship Troopers was greenlit.

Compared to Tippett’s earlier effort in photorealistic digital creatures — Jurassic Park — Starship Troopers presented considerable challenges: not only it required a far more massive number of digital effects, but it would represent fictional entities without an actual point of reference from reality. Tippett explained: “we’d had concrete reference points for [the Jurassic Park] dinosaurs; and when the weight and the joints of a real animal — even an extinct one — are available to you, you pretty much know what to do with it digitally. But when you’ve got something that’s never really existed, such as the insects of Starship Troopers, suddenly the tail is wagging the dog. We had these great Bug designs that Craig had come up with, but trying to figure out what these creatures could do — what, for them, could be a realistic gait, or a lifelike action — became an enormously complex enterprise.” In addition to that, the creatures would be shot in full daylight for most of the film, rendering the process even more challenging.

At least one hundred digital artists — from animators, to compositors, to other technicians — worked on Starship Troopers to bring the Bugs to life. Each animation sequence started with a series of low-resolution animatics. Digital scans of the maquettes sculpted by Peter Konig and Martin Meunier provided the wire-frame of the models, which were then finalized. An exception to this was the Tanker Bug, who was created in Softimage by Blair Clark without going through the digitizing process. All models were then refined in Softimage, and set up with kinematic chains, which enabled them to be animated. Paula Lucchesi and Belinda Van Valkenburg were responsible for the color scheme and surface texture of the creatures.

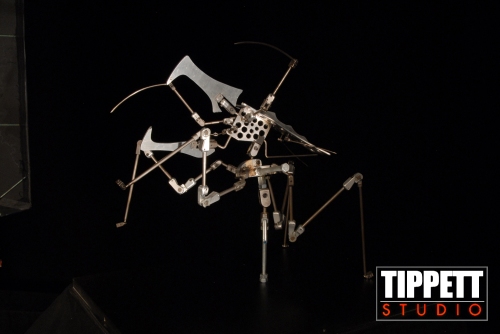

Two animation techniques were used by Tippett’s team: for the most part, key-framing animation was used, including the entirety of the sequences involving the Tanker Bugs, the Hopper Bugs, and the Brain Bug. A considerable number of sequences involving the Warrior Bugs also used the Digital Input Devices (DID, originally standing for Dinosaur Input Device), a Tippett Studio invention first experimented in Jurassic Park and Tremors 2: Aftershocks, built by Merrick Cheney in the shape of the Warrior Bugs. The DIDs are small-scale articulated models, fitted with motion sensors that transfer the movement applied on the DIDs to the digital models being animated.

For Starship Troopers, the DIDs were refined: their sensibility to motion was increased, enabling them to register finer animation cues. Tippett told VFX HQ: “we’ve refined the DID since Jurassic Park, in the overall cleanup of the design. Craig made sure that the DID would be much more responsive to the animator’s movements… all of which was preparing for the massive amount of animation that was to be done on the DID for Troopers.” Two types of the devices were used: one functioned in real time, and was used for quick background shots of the Bugs; the other was used for more detailed sequences and brought the animation process to a method similar to that of stop-motion animation. To link this second type of DID directly to Softimage, the effects team wrote a new hardware interface board and a specialized software. “Much of the way the bugs moved was dictated by Craig’s designs,” Tippett said. “We did a lot of animatics, and assigned the Bugs weights and the extent of their movements to come up with an animation design, to see how realistically these beings could move and run and attack.”

Accompanying Tippett Studio’s digital effects was a wide array of practical creature effects devised by Amalgamated Dynamics. The ADI crew built a series of close-up puppets, insert puppets and full-size puppets for the project. The practical creatures provided realistic contact with the actors, and also served as background dressing. Capturing certain shots entirely in-camera also decreased the pressure of having to perform them digitally. Tippett related: “most of that centered around contact, like when you actually see a real person about to be chopped in half and the beak of a bug. That was a real human until the chomp happens.”

It is actually an ADI creature effect first appearing in the film: the Arkellian Sand Beetles — seen on autopsy tables as part of a biology lesson (hence their production nickname of ‘Dissection Bugs’). Eight three-feet long, two-feet wide creatures were built; each one was composed of 12 main parts, among which the head and legs — moulded in translucent skinflex, a more flexible type of urethane. The body was instead moulded in urethane. Among the props, one was a hero Beetle which could be filmed in full detail; it was painted with acrylics and detailed with horse hairs (each individually ‘punched’ into the skin). Its insides were rendered with ultraslime, methocel and nylon — other than silicone organs. The internal structure was held together by a thin silicone membrane placed under the urethane abdominal shell, which was severed during filming to simulate the dissection. To create the effect of pressurized internal organs, a simple internal air bladder was inflated manually with an air rig.

The first Klendathu Bug design to be approved was the one seen the most in the film — the Warrior Bug, “an eight-to-ten-foot-tall insect infantryman,” as described by Hayes. The design is entirely devoted to its function, with a weaponized anatomy: the Warriors use their enormous jaws and their sharp, mantis-like arms to brutally slaughter their targets. Their slender anatomy also guarantees agility during combat. The fundamental silhouette of the Warrior Bug was inspired by rhinoceros beetles — such as the Hercules beetle — and their peculiar horns. “The Warriors were modeled on those big rhinoceros or elephant beetles, which have huge chopping ‘jaws’,” Hayes related. “We gave them two attack claws up front to help them draw people into their jaws.”

The four legs configuration was “purely practical,” according to Hayes — devised to render animations less complex. Hayes continues: “four legs meant that our animators needed to spend only half the time moving them around.” Tippett added: Craig made sure they only had four, because we had so many Warriors to deal with; keeping the number of their legs down would give us a bit of an advantage. Making them walk was the hard part. “We were dealing with a heavily textured landscape, so the footfall patterns, the shifting of weight and all of the physical attributes had to constantly be worked on and adjusted. With every step, they had to either go up, around or over a rock.”

An aggressive colour scheme completed the look of the Warriors. Hayes explained: “to make them look really mean, we gave them graphic splash patterns reminiscent of other predatory animals or insects. The Warriors have yellow-orange stripes like wasps and tigers, and a red strip on top of their heads and jaws so you’ll hopefully understand which end’s up. We also avoided big round soft shapes; everything is pointed. If one stepped on your toe by accident, it would hurt.” He also added: “we also had a chance to tweak the colorization of these Bugs during the test. Paula Lucchesi, who led the paint jobs on all of the Bugs, originally came up with a dark red pattern for the Warriors. Later, we decided to change it to yellow — the coloration you see on wasps and yellowjackets. It is a natural warning sign, signaling other creatures to stay away.”

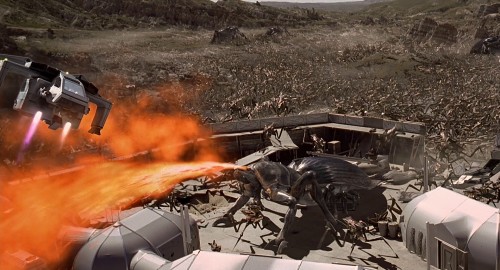

An animation tool that proved crucial to rendering swarms of Warrior Bugs was the so-called ‘Dynamation’, used in scenes such as the Tango Urilla carpet bombing and the Whiskey Outpost attack. Software developer Doug Epps explained: “normally, Dynamation is utilized to generate things like smoke clouds or jet exhausts; but Dynamation also allows you to do procedural animation of points and particles — a capability that was critical in laying out the swarms. We knew we had to do hundreds, or even thousands, of Bugs in some shots, and we certainly didn’t want to have to hand-animate all of them. So we used Dynamation’s particle systems — tweaked with software written by Eric Leven and Darby Johnston — to generate dozens of little dots that we could then apply en masse to a plate. Dynamation gave each Bug its own radius and terrain maps and maximum velocity vectors, which allowed it to maneuver over the landscape of a given scene without hitting other Bugs or obstacles such as rocks. That process really saved us. We’d still be doing swarms if it hadn’t been for that software.”

To differentiate the Warriors, specific animation cycles were assigned to each one of the ‘dots’, and some of the creatures were also slightly downsized or oversized. Hand-animated ‘hero’ Bugs were placed in the foreground, whereas less-detailed Bugs — called ‘Jacks’ — were positioned in the midframe and background. “We called them Jacks,” noted Danny Boyle, part of the visual effects crew, “because these particular Warriors were going to be tossed up into the air by the force of the explosions, just like a child’s set of jacks.”

The most articulate sequence employing Dynamation was the Whiskey Outpost attack, one of the first to be taken on. Epps recalled: “on any effects film, we like to get the big shots out of the way first. Anything you learn at the front of the schedule makes subsequent shots of the same nature a lot easier to accomplish. So we tackled the first two swarm shots in that sequence right away.” Nearly a dozen swarm shots was made for the sequence and carefully detailed to be as realistic as possible, such as dust or shell parts being blown off. “These elements were either CG or real elements filmed against greenscreen,” said Doyle. “The dust kicked up by the Warriors was a separately photographed element, as were a lot of the squib hits and gore effects you see on the Bugs.” The second swarm did not have to move in separate paths; as such, “instead of run cycles,” Epps said, “the animators set up ‘milling about’ cycles, which were inserted over the Dynamation-generated Bug dots.” Rendering time for the swarm shots clocked in an average of 60 hours per frame first, then 25-30 hours as the crew became accustomed to the process.

Two full-size animatronics of the Warrior Bugs were provided by ADI. They were engineered by George Bernota, and based on full-size sculptures by Steve Koch and Brent Armstrong. Their shell was moulded in fiberglass and painted; soft skinflex portions were the finishing touches, and covered jaw, wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints. Both were driven by a combination of pneumatic, cable-controlled, and hydraulic mechanisms. ‘Snappy’ — nicknamed by the crew after its articulated jaws — was an insert upper-torso animatronic, detailed from the shoulder area to the head. The nine-feet tall puppet featured fully articulated front legs, arms, jaws, and eyes, and was hydraulically operated for head rotation. In order to properly lift actors as certain sequences requested to, its internal structure was built in steel. A collision avoidance program also prevented the puppets from damaging themselves.

Where Snappy only needed three puppeteers, the other animatronic — a full-body creature, nicknamed ‘Mechwar’, needed five. Measuring a total of 15 feet in length and 10 feet in height, Mechwar was able to perform a wide range of at least 30 separate movements. Its head was hydraulically powered — as was its thorax, which combined hydraulic, pneumatic and electrical systems. The jaws and arms were puppeteered with cables and hydraulics, whereas the legs were maneuvered via rods. Head, jaws, arms and the creature’s smaller parts (such as the eyes) were puppeteered separately. The controllers were custom-made small-scale armatures that corresponded, section for section, to the full-scale animatronics. Fitted with motion sensors, similarly to Tippett’s DIDs, the devices could transfer the movement applied to them onto the puppet. Gross body movements were provided with a simple support crane attached to the Bug’s thorax. Built by John Richardson’s department and operated by eight crewmembers, it could perform upward, downward and rotational movement.

Numerous full-size models were constructed to portray dead Bugs. A total of 15 props portraying the deceased Warrior Bugs was built: five charred creatures and ten bloody carcasses, riddled with gunfire. Co-founder of ADI Alec Gillis said that “those were scaled-up from the maquettes, moulded in silicone, seamed, and cast out of fiberglass. We decided to do the full-scale Bugs modularly in order to quickly pop them together as needed, and each Bug was broken down into 34 separate pieces. We also made backup pieces, in case of location damage. With 34 pieces for each dead Warrior, multiplied by 15 dead Warriors, multiplied by backups, just manufacturing these things turned into a huge job.” Other minor creations were insert arms. Made of fiberglass and four-feet long, the appendages were maneuvered offscreen via handles on the shoulder end. The Bugs’ entrails were created with a combination of chopped latex and foam rubber scraps. The blood was instead methocel, tinted green, orange — in the case of the Tanker Bugs — or cream-like — in the case of the Brain Bug (the reason for the different coloring within the same species was not addressed — neither within the film nor by the filmmakers).

The painting process revealed itself to be far more challenging than originally expected. Despite the fact the paint schemes had already been elaborated by Tippett Studio, ADI had to scale them up. Tom Woodruff Jr. commented: “it’s a different ball game when you’re interpreting the coloration of painted reference models into full-scale props. Once we applied the Warrior’s initial paint job to our magnified versions, it suddenly looked toy-like, just because of the immense size of our Bugs.”

The final paint schemes were enhanced with a lacquer seal, then toned down and ‘aged’ using sandpaper, dust, and other tools. The burned texture on the charred Bugs was obtained by cutting the models in selected areas, and applying liquid urethane — precoloured with black tones — that “foamed up and gave the Bugs a crinkled, charred texture,” as told by Woodruff. “We also peeled back the Bugs’ exoskeletons and added bits of coloured foam inside to give them a more charred appearance. Then we touched everything up with black paint.” Koch added: “Phil Tippett came to the shop one day to give art direction on the painting and finishing, emphasizing a scuffed up worn look to the Bugs.”

The Plasma Bug represents the heavy artillery of the Bugs: by rearing its weaponized abdomen, it shoots plasma projectiles into the sky of Klendathu. Hayes said: “we spliced together the biologies of real stink bugs and fireflies to come up with the Plasma Bugs — gigantic creatures that could eject plasma from their lower abdomens into a planet’s upper atmosphere, resulting in spaceships being knocked out of orbit or asteroids off course. The Plasma Bugs became the heavy artillery of the aliens.” Due to their size, their limbs are proportionally thickened; and since the plasma projectiles are ejected from their enormous abdomen — the last pair of limbs is bigger than the others, in order to lift the ‘biological cannons’ into a stable upward position.

In the early encounter with the Plasma Bugs, the creatures are seen ejecting their deadly weapon into the skies of Klendathu. Layers of computer-generated transparencies were provided by the art department to render the translucent abdomens of the creatures, with the plasma projectiles rendered with RenderMan and Dynamation.

A deleted scene from the film showed that the Plasma Bugs’ projectiles were energy-charged larva-like Bugs; the grub-like design devised by Hayes was even sculpted in full-size by the ADI crew, but the sculpture was left unused.

The impressive Tanker Bug is an enormous armoured beetle-like creature with a lethal long-range acid spray; it represents World War II tanks. “They’re [like] half-track tanks,” Hayes explained. “They have multiple legs — a big set up front, and then a row of six small ones. They’re mobile plasma sprayers, like flame-throwers.” The structure of the Tanker Bugs is mainly inspired by earth beetles, with thickened locomotory limbs to support the creature’s mass.

The Tankers also have enlarged claws or toes to aid their stability when walking. Their name is derived from their organic long range weapon, violently ejected from an orifice in their forehead region: a flow of “corrosive acid ignited by organic sparkers near their mouths, spewing out a cross between an acid bath and a flame-thrower.” The final design applied cosmetic changes in regards to the maquettes — such as an additional pair of locomotory limbs.

The Tanker’s acid spray posed a particular challenge for the crew. Larry Weiss, part of the digital effects crew, recalled: “in designing the look of the Tanker spray, we looked at a lot of lava footage for reference. It wasn’t supposed to be lava, but it was meant to have that kind of consistency. We played around with Dynamation for a long time to come up with the final look.” The last detail was a layer of heat distortion to suggest the extreme temperature of the acid. Transparency layers were used to portray the exploding Tanker after Rico inserts a grenade in its damaged hide. Doyle commented: “you see all of these multicolored organs inside what is left of it. The art department used a separate, gutted CG Tanker model for that shot, showing its exposed innards as the Tanker rocks back and forth to a halt.”

For the scenes where Rico is seen on the back of the Tanker Bug, ADI constructed two fiberglass shells, sculpted (in green foam) as well as painted by Bob Clark. They were joined together to form the back plate of the Tanker Bug. The actor was attached to the shells with thin wire tethered to a belt. To portray the wild movements of the Tanker as Rico tries to penetrate its hide with gunfire, a twenty-feet long tractor was installed beneath the shell through a system of metal supports, hydraulic rams, and a gimbal. Two crewmembers puppeteered the shell.

The air troops of the Bug army are represented by the Hopper Bugs, “capable of gliding on air currents and shearing off human heads.” The design was obtained by reverse-engineering the Warrior Bug design, with several changes and additions — such as the wings, appropriately large to support the creatures in flight; the legs, structured for long jumps (or ‘hops’) and for take-offs; and a less angular shape of the main jaws.

The Hopper Bugs also sport a considerably different color scheme, which is mainly composed of an iridescent green — inspired by certain species of beetles, such as the goldsmith beetle — in contrast with the Warriors’ more opaque configuration. Hayes said: “the Hoppers have translucent wings that fold up and fit inside their carapace. They’re greenish-blue, with a metallic reflective surface that gives them a futuristic, aerospace feel.”

The Hopper Bug was “one of the most challenging Bugs for the art department,” said Lucchesi, “because of its iridescent surface quality. It is beautiful to look at in the real world, but very difficult to replicate in the digital one. Our department worked with Doug Epps to come up with a custom, metallic surface shader. By applying that shader and experimenting with red-green-blue texture maps of varying degrees of intensity, we came up with a refractive quality on the Hopper’s body that was pretty successful. We used displacement to deform the surface so that light would catch certain areas of the wing more than others, giving them a wispy, delicate look. Then the compositing department blurred whatever environment was behind the wings to suggest their semi-translucent qualities.”

Animating the Hoppers was considerably difficult due to the fact they had to be affected by small changes in wind currents during flight; as such, they made small course changes, in a manner similar to real flying insects. Tippett and Hayes initially established ‘flight rules’ for the creatures: “when Hoppers decelerated, for example, they flared their wings out. When they dove, they adjusted the attitude of their wings. So there were definite rules — but other than that, the animation of the Hoppers was done mostly by feeling.”

Due to the Brain Bug’s inability to travel by itself, Hayes devised the Chariot Bugs as its “transporters” — small creatures with a plated dorsal region, able to coordinate their efforts to support and move the considerable weight of the Brain Bug across the nests. Hayes commented on the design: “because [the Brain Bug] is so fat, it is relatively helpless, physically, and rides around on the backs of little courier insects, which also act as information gatherers. We called those Chariot Bugs.” He also said: “there are the Chariot Bugs, the Brain Bug’s entourage, which are 4′ long cockroach-like things that band together to form a moving carpet which supports him. They’re like comic relief.”

A full-size dummy of a dead Chariot Bug crafted by ADI foreshadows the Brain Bug. The digital versions seen in the climactic nest scene were animated with the intention to portray them as worshipful servants of their master. Character animation supervisor Trey Stokes said: “they adore the guy. We tried to suggest that by animating moments where the Chariot Bugs’ feelers are touching and stroking the Brain’s body. To suggest that they are also a form of bodyguard, we animated one to stand guard over a rifle that Zander has dropped. It is a subtle throwaway, but it’s there.”

The Bugs’ strategic mind is the Brain Bug. Appearance-wise it channels the vague description provided in Heinlein’s novel, with an enormous, bloated body and atrophied limbs. Partial inspiration for its design was found in Lovecraft’s descriptions of the Great Old Ones — stories Verhoeven is fond of. “The Brain Bug is a pulpy, horrible creature that Paul always thought of as a God-king, Cthulhu-type thing,” Tippett revealed to American Cinematographer. “He does the nasty job of sucking people’s brains out, so there are some human sacrifices happening.”

The base reference for the creature design was a queen termite. “Paul wanted it to look like a queen termite,” Hayes said. “He’s into biology, so the Brain Bug looks a bit like a pus sack with flesh-colored, undulating sides that resemble a big intestine.” He also commented on the design: “I thought it would be interesting to have pulsing ripples periodically moving just under the flesh on the top of the Brain Bug’s head — an effect we dubbed ‘the meat wave.’ For his face, we hit on using multiple eyes, like a tarantula’s, and a slitted, sexually suggestive mouth organ. From that unfolds a hollow, pointed proboscis — another sexual suggestion — which can spike the top of a human head and suck its brains out.”

The digital Brain Bug was modeled by Martin Meunier and Merrick Cheney, and animated by Jeremy Cantor entirely with key-frame. The meat wave effect was achieved with procedural software shaders, written by Epps for RenderMan. Stokes noted that “the tricky part was making sure that the meat wave movement was adjusted to the overall animation of the Brain Bug, so that the wave didn’t change the character of the Bug’s animation. One way Jeremy approached that was purely procedural — he got in there and digitally grabbed the Brain Bug’s flesh and warped it all over the place. For the actual wriggling mounds of flesh, Jeremy used another shader, created by Doug Epps, called ‘Blorph’. If Jeremy wanted one of the Brain Bug’s cheeks to hit the ground and jiggle for a second, Blorph would allow him to do that. That piece of software, combined with the meat wave effect, gave the CG Brain Bug a convincing look of weight and fleshiness.”

When the Brain Bug is captured, it is dragged outside the nest inside an enormous net. The challenge of these shots lied in animating the net and the Bug so that they would not overlap. Lucchesi explained: “the CG net had to be close enough to the surface of the Bug that it wouldn’t look as if it was floating, but far enough away so that it wouldn’t appear that the net was going through the surface. We also had to be careful when casting shadows of the net onto the Brain Bug’s body so that they wouldn’t emphasize any contact problems.” Tippett added: “Jeremy Cantor, in particular, was great at finding just the right level of procedural and texture-based animation to make the CG Brain Bug look like he was encased in that net, while at the same time making sure that the Bug did not absorb the netting beneath the surface of its skin.”

ADI constructed a massive insert puppet of the Brain Bug — the most ambitious practical creature of the project. Since the full body would only be brought to the screen digitally, only the head of the creature was built; it was 12 feet tall and 10 feet wide. The creation of the animatronic started with a full-size sculpture — in green foam and clay — by Bob Clark. The face of the Brain Bug was sculpted separately in clay and other materials by Steve Koch. The head was moulded in separate pieces of fiberglass, which were joined together to form the underskull. The structure was then covered with foam latex skin — again cast in pieces due to the sheer size of the animatronic. The face was instead moulded in skinflex and positioned over the articulation mechanisms.

Gillis commented: “Craig Hayes did a remarkable job designing that face. It was detailed with long, thin, paddle-like appendages near its mouth, called feeder claws. It had eight eyes and a huge, vertically slitted mouth. All of those things had to be replicated in the full-size puppet. We made the feeder claws out of fiberglass, operated by radio control mechanisms. The eyes were cast of high-gloss urethane, misted with a silicone oil during filming to make them reflective and alive. The sphincter-like mouth was also made of skinflex. We attached air bladders on either side of the underskull, which could be manually operated by little hand bellows to make the Brain Bug look as if it was pulsating.”

The practical version of the ‘meat wave’ effect was designed by David Penikas. He engineered and built an eight-feet long and two-feet wide endless conveyor belt system, which followed the curvature of the Bug’s upper skull and was installed under the skin. Two rollers with gripping servomotors were placed on the creature’s brow area and on the back of the head, connected by the belt — which was covered with crescent-shaped pillows. A motor equipped with a speed controller produced the rippling effect by running the conveyor belt, whereas the pillows damped its actions. The creature was also supposed to express emotions through its bodily language. “One of Paul Verhoeven’s big concerns,” Woodruff said, “was that we be able to get a variety of expressions out of this face. That was one of the difficult challenges, to make it not only look fearsome but fearful as well.” Five puppeteers controlled the Brain Bug’s movements from inside the animatronic itself; gross movements of the entire head were provided by a support rig the puppet was attached to.

The Bug’s segmented proboscis was puppeteered with cable mechanisms. Yuri Everson, part of the ADI crew, recalled: “we made a number of triple-jointed, cable-controlled palps, operated from inside the puppet head, through what looked like a little t-shaped motorcycle handlebar.” The exterior of the proboscis was moulded in translucent vacuform and then airbrushed. For the scene where Carmen severs it, a pre-cut tip was attached with superglue, and a hollow tube was inserted — to pump colored methocel, which simulated the creature’s blood spurting out.

The brain-sucking effect seen when the Brain Bug kills Zander was a collaboration between ADI and Kevin Yagher Productions, the gore effects provider for the film. Technician Bryan Blair commented: “working alongside ADI, we did that in two stages. For shots where it’s obviously actor Patrick Muldoon looking horrified, we came up with a mohawk-type wig for him, with a fake silicone wound attached to the top of it. ADI took off the top of one of the hollow vacuformed palps and attached it to our fake wound and hair appliance. At the same time, we’d hidden flexible, hollow plastic tubing, about an inch in diameter, under Patrick’s hair. That tube trailed down behind his back and into a plastic bucket, where we’d deposited this sausage-like rope of silicone ‘flesh’ that was attached to a string and drenched in stage blood. We ran the string out the opposite end of the tubing and into ADI’s hollow spike. On ‘action’, Patrick started to grimace while I pulled the string, yanking the sausages up through our hidden tubing into the translucent spike, making it look as if Zander’s brains were being sucked through the palp.” The sequence was completed with two puppet heads of Zander, respectively simulating his pain as the palp pierces his head and his death.

“It’s interesting how the world is divided between people who are either terrified by insects or terrified by reptiles,” Tippett said in retrospect of the Bugs. “I never was subject to the fear of reptiles, but insects always gave me the creeps. Making this film was no catharsis.” Ultimately, Starship Troopers presented an array of groundbreaking effects that carved their place in Creature Feature history and inspired generations of films after them; no film before had tried such a massive quantity of creature effects. “I’m exhausted,” Tippett said, “but it worked out pretty well.”

Would you like to know more? Visit the Monster Gallery.

Awesome that you’ve covered this film, it’s one of my favourites!

Il film in sè non mi ha fatto impazzire,anzi.Tuttavia gli Aracnidi di Klendathu mi sono piaciuti molto!

Se non fosse stato per l’articolo non mi sarei mai accorto che il “Bug Plasma” e il “Bug Thanker” fossero due tipi distinti di Insetti (credevo fossero la stessa tipologia),nè che i “Bugs Chariot” fossero i trasportatori dell’Insetto-Cervello (li avevo interpretati come larve di quest’ultimo).

Peccati per i guerrieri alati,si vedono in un paio di occasioni e alla svelta.

Mi domando se il romanzo da cui il film è tratto si possa trovare ancora in giro…

Il Romanzo è conosciuto in Italia semplicemente come “Fanteria dello Spazio”, puoi prenderlo comodamente su Amazon.

Really great piece. I’m gonna go back and watch the movie again, now.

[…] approximately to 200 animation shots, a number that rivaled the Tippett Studio shot count in Starship Troopers — with the important difference of a much lesser time in which the crew could produce them. […]

[…] previous moulds. Recycled moulds included portions of creatures from the Tremors films, Starship Troopers, Alien: Resurrection, and Dragonball: Evolution. Originally, Kate stumbled upon the “pod […]

[…] MonsterLegacy […]

Verhoeven and Neumeier are talentless hacks

What an insightful, on-topic comment!