Tang Wei: The Look of Love

BY

Phuong Le

A look at the explosive debut of Tang Wei.

Lust, Caution plays as part of Starring Tang Wei at 7 Ludlow.

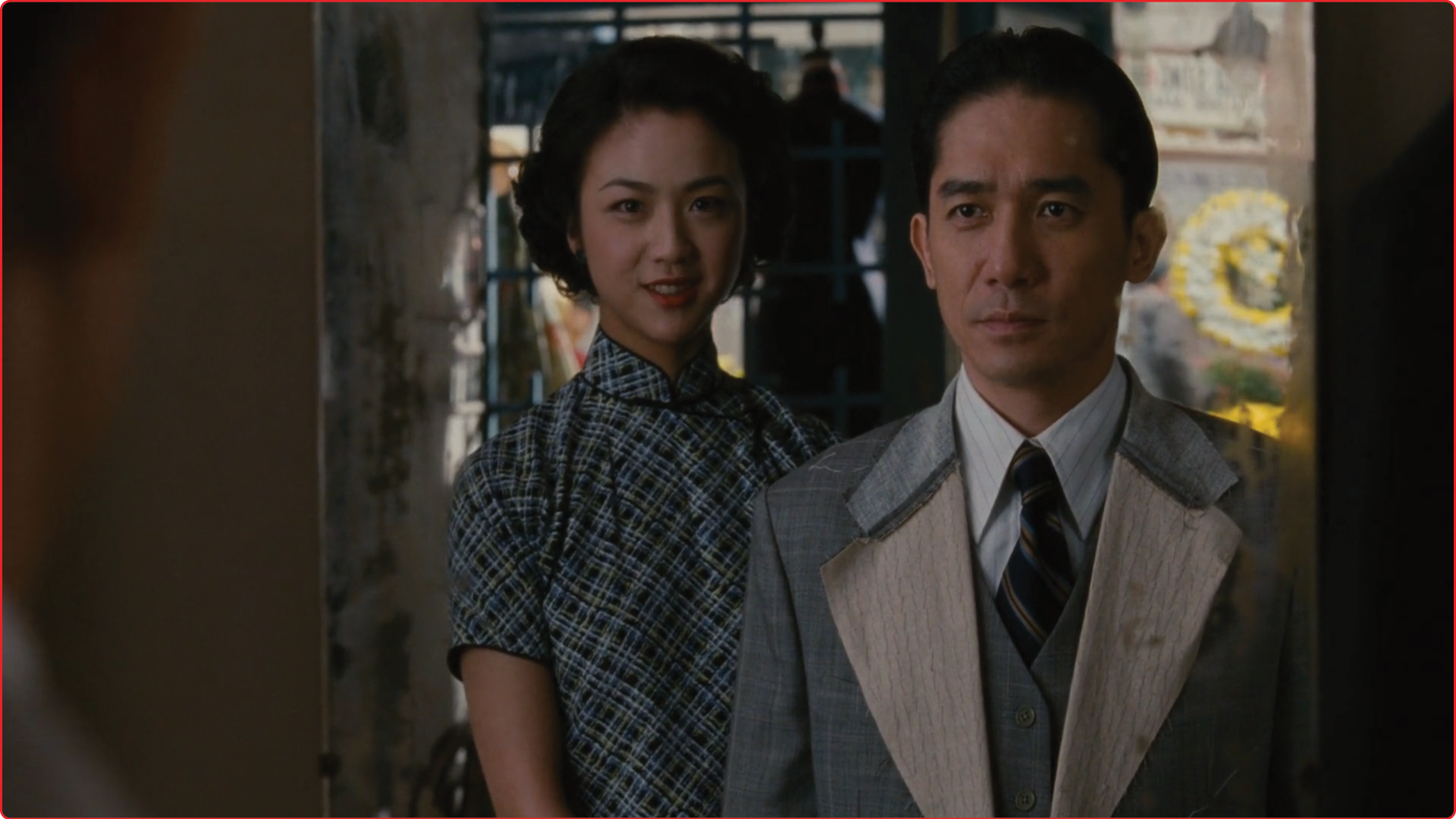

If Tony Leung Chiu-wai has been praised for his ability to act with his eyes—there exists a YouTube video essay on the subject with over a million views—Tang Wei, in her explosive acting debut in Lust, Caution (2007), shows an uncanny ability to embody that ineffable state of being looked at. Adapted from Eileen Chang’s eponymous novella, Ang Lee’s noir-inflected espionage period drama earned notoriety at the time of release for its explicit sex scenes between Tang and Leung, yet at the center of this erotic cat-and-mouse game lies a complex system of gazes. In the same way that spying is akin to acting, between duplicitous lovers, fucking can also be a kind of performance, a corporeal dance on the edge of catharsis and deceit.

It’s 1942. Following the Japanese takeover of Shanghai, everyone is being watched. Moving from the outside of a residential compound which houses high-ranking collaborationists to the plush interior where the clackety-clack of a mahjong game bounces through the corridors, the opening scene of Lust, Caution evokes the stifling, panoptic reality of life under colonial occupation. Even amid this seemingly convivial atmosphere of female gossip—far from the crowd of guard dogs and security police—all eyes are on Tang’s Wong Chia Chi, a fresh-faced drama student who has been recruited as the Resistance’s honey pot. Dressed in elegantly tailored qipaos, she has adopted the seductive guise of Mak Tai Tai, the wife of an export-import businessman, and successfully charmed her way into the household of Mr. Yee (Leung), a vicious agent for Wang Jingwei’s puppet government whom she has been positioned to assassinate. At this moment, her target has yet to enter the scene, but the way the camera circles around the prying glances constantly darting her way suggests that, for a spy, the stage curtain is rarely drawn.

Lust, Caution (2007)

In the same way that spying is akin to acting, between duplicitous lovers, fucking can also be a kind of performance, a corporeal dance on the edge of catharsis and deceit.

The male gaze—and its desire to fracture the female body into sexualized objects for the male characters, the camera, and ultimately the spectator—has long been a popular, if contested topic of discussion in film criticism. But what is less talked about are screen roles that reflexively acknowledge the innate and intricate spectacle of performing feminine archetypes. How do we read characters who willfully refashion themselves after the scopophilic pleasures of others? To render them as mere fragments of male fantasy is too simplistic. What makes Tang’s presence in Lust, Caution especially beguiling is the complex and interlocking tension that exists between the real-life actress, the onscreen drama student Wong Chia Chi, and the final mirage of the sophisticated Mak Tai Tai; it’s the kind of transgression that rejects facile markers of empowerment, delivered by the then-27-year-old Tang with astonishing range.

Working under the Resistance, Wong Chia Chi operates according to the patriarchal orders of her superiors, but her double life as Mak Tai Tai is also anchored by her remarkable inner will. A tantalizing mix of beauty, docility and sultriness, Mak Tai Tai is resourceful but economical with her words; she possesses just enough mystery to pique Mr. Yee’s interest. Tang’s palpable magic as an actress manifests in the way she hints subtly at the calculated machination of emotions hidden beneath the submissive playacting. Those big, almond eyes—which so often avert the direct gaze of others—are always cunningly alert, open to opportunities for entrapment that may lead her dangerous prey to his doom.

Lust, Caution (2007)

Such knowing manipulation is especially fascinating to behold in the brief but pivotal sequence where Mak Tai Tai, having caught Mr. Yee’s attention, takes him to her favorite tailor. Emerging from the fitting room after trying on an altered qipao, which tightly enwraps her body, Mak Tai Tai regards herself in the mirror while Mr. Yee’s eyes leisurely trace her lithe frame. When Mr. Yee asks her to keep the dress on, as Mak Tai Tai returns his gaze, what is reflected onscreen is not merely male lust but also the craftiness of female allure. In this seduction ritual, she is the metteur en scène.

Throughout the film, Wong Chia Chi is often shot against mirrors and within doorways, compositions that not only denote her fragile in-between position between warring forces, but which also mimic the threshold of the stage. After the pair have embarked on their torrid affair, Mr. Yee has Mak Tai Tai chauffeured to a sleazy establishment frequented by Japanese officers looking for cheap thrills. In this palace of sin, he looks on as his mistress serenades him with a well-known Chinese love song, “The Wandering Songstress,” her exquisite movements framed by Japanese-style screen doors. Popularized by movie star Zhou Xuan, who first performed the melancholic melody in Street Angel (1937), the tune speaks of romantic yearnings that thrash against the tragedy of wartime. Under the myriad layers of make-believe—here’s a musical performance from a woman who is also pretending to be someone else—is the treacherous topography of looks. While absorbing the wistful gaze of Mr. Yee, Mak Tai Tai’s song also alludes to her own voyeurism. After all, Wong Chia Chi routinely frequents cinema halls, a character detail absent from Chang’s source material. If the mystique of Tang’s presence lies in the deliberate withholding of access to her character’s psyche, these sequences in which Wong Chia Chi bodily reacts to film scenes are perhaps the closest we can come to getting under her skin.

Besides their acrobatic explicitness, the sex scenes between Mr. Yee and Mak Tai Tai were also condemned for their violent, sadomasochistic streak, with women’s groups such as The Women Film Critics Circle labeling the adaptation a “Hall of Shame” film. Such criticism is not without merit. After all, their first sexual encounter where Mr. Yee whips Mak Tai Tai with his leather belt before forcing his way inside her is very much the equivalence of rape. Nevertheless, what interests me about these controversial sequences is how the power dynamic of looking and being looked at functions in moments of carnality. During their first tryst, Mak Tai Tai once again puts on a show for Mr. Yee. While she forces him to sit and watch her slowly taking her stockings off, the distance between the actress and the audience is violently erased. Her performance is cruelly cut short, as Mr. Yee suddenly gets up from his seat and throws her against the wall. Nevertheless, in their subsequent rendezvous, Lee frequently shoots the entangling of their naked bodies from a bird’s-eye view, as if suggesting the lovers are being watched by omnipresent forces. It’s a stylistic choice that heightens the paranoia of their relationship, as well as the performative nature of sex itself. In the heat of climax, is Mak Tai Tai actually present, or is she merely replicating the sexual moves for which she has been trained? If in the beginning, Mr. Yee wordlessly forbids Mak Tai Tai to look at him—he often forces her face against the bed sheet—by their final encounter, she is the one who places a pillowcase over his face as she writhes atop his torso. In the realm of the senses, the act of looking becomes more nakedly revealing than ever.

Fifteen years since her infamous debut, which led the actress to be blacklisted in mainland China and unable to work for three years, a fate not endured by her co-star Leung, Tang’s latest femme fatale in Park Chan-wook’s Decision to Leave (2022) is a welcome reminder of her unique capacity for teasing out the eroticism of the gaze. Playing a possible murderess who delights in being spied on by the detective tasked with investigating the death of her husband, Tang brilliantly articulates the strange power that is exerted by an object of obsession. In challenging the rigid binary of submission and empowerment, her characters complicate any rudimentary perceptions of the gaze. Under her spell, we simply cannot look away.

A Vietnamese film critic based in Paris, Phuong Le is a regular contributor to The Guardian, Sight & Sound, and other publications.

Decision to Leave (2022)